Image from 'Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series' Read more ...

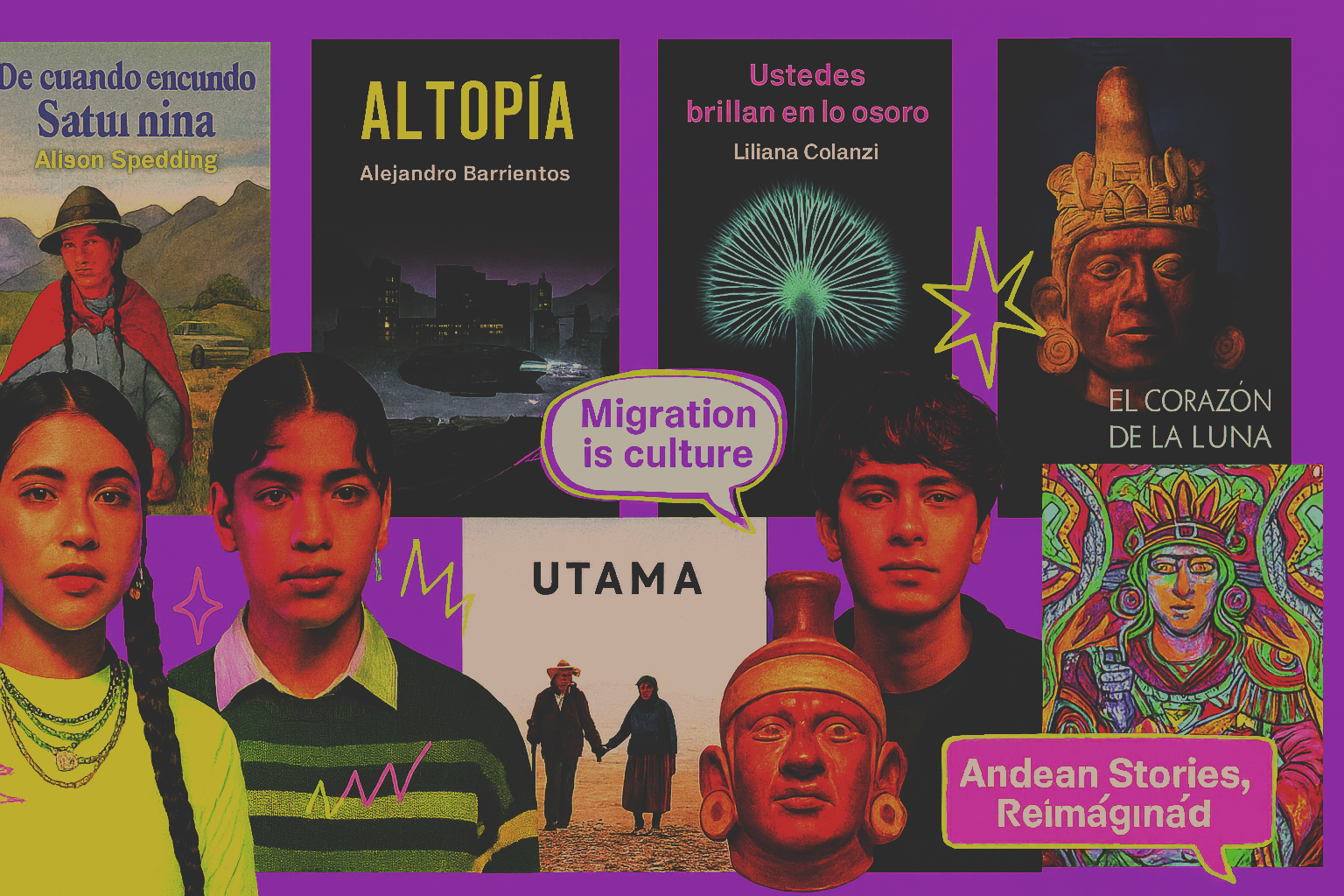

Ever since Europeans “discovered” the so-called New World, Latin American writers have been reimagining what it means to move—across oceans, across borders, and across worlds. From Christopher Columbus and Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca to José Martí, Ariel Dorfman, Luis Sepúlveda, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Chicana icon Gloria Anzaldúa, storytelling in the Americas has always been a journey. And human mobility isn’t just a thing of the past—it’s one of the defining experiences of our time. Even within a single country, migration reflects the tangled realities of our globalized world. In Peru and Bolivia, for example, recent portrayals of Indigenous migrants reveal a shift in how we understand knowledge, identity, and belonging—challenging old Western ways of looking at the so-called “subaltern” and sparking fresh debates about race, class, and the politics of knowing.

My research dives into the aesthetics of migration—how art, literature, and film don’t just tell migration stories, but shape the very way we think about them. I explore how Andean narratives imagine the migrant, and how these cultural works push back against colonial ways of knowing. This is what scholar Walter Mignolo calls “epistemic disobedience”—the refusal to simply fit “the other” into Western frameworks, and instead embracing multiple, non-Eurocentric ways of understanding the world. In other words, it’s about listening to the many voices that global history has tried to silence—and discovering how they rewrite the map of knowledge itself.

Current Research

My current work brings together three seemingly distant worlds: Post-Cold War Andean narratives, the cultural imagination of the Anthropocene, and the rise of “Andean-Pop.” Yet all three converge in the same historical moment, shaped by overlapping displacements—not only the movement of people across borders, but also translations into virtual spaces and speculative worlds. From the ecological visions of Anthropocene science fiction to the unapologetic flair of cholo-pop aesthetics and the immediacy of social media interventions, these projects map an Andes in transformation—politically, culturally, and imaginatively.

FORTHCOMING . . .

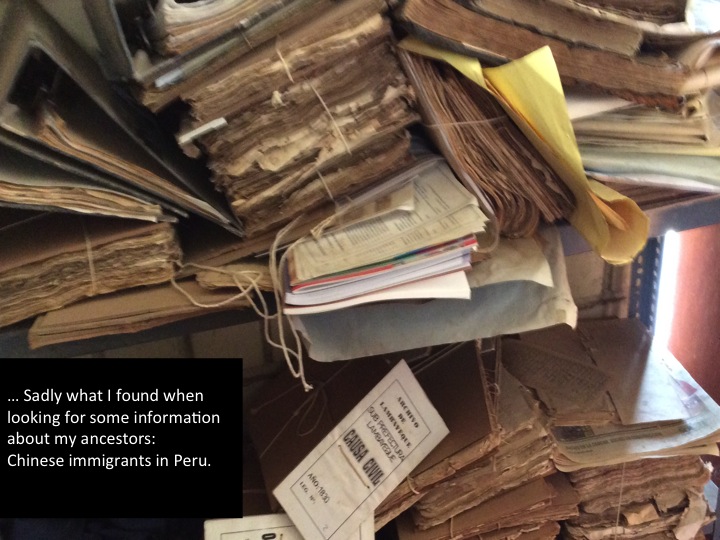

My forthcoming book Affective Economies of Migration: Chinese-Peruvian Bonds, Loves, and Friendships reveals the intimate side of migration, uncovering how the Chinese diaspora in Peru transformed bonds of love, friendship, trust, and kinship into powerful forms of economic and social capital. Moving beyond conventional historical and literary narratives, the book shows how affective relationships shaped pathways of social mobility, wove communities together, and redefined the collective future of Chinese Peruvians. Blending history, literature, and cultural analysis, Affective Economies invites readers to see emotion not as a private matter, but as a driving force in economic and cultural transformation across the global diaspora.

Previous RESEARCH

My first book, Fictions of Migration: Aesthetics of Displacements in Peru and Bolivia invites readers into the shifting cultural landscapes of the Andes, where stories of migration reveal much more than movement across borders. Drawing on powerful works of 20th- and 21st-century cinema and literature, this book uncovers how artists in Peru and Bolivia imagine the migrant experience in ways that both clash and converge.

In Peru, migrants often appear through haunting tropes of monstrosity; in Bolivia, they emerge as keepers of collective knowledge and community wisdom. Yet, despite these contrasts, both traditions recognize migrants as bearers of insight—agents of cultural transformation rather than mere victims of crisis.

By weaving together politics, aesthetics, and the lived realities of displacement, Fictions of Migration points at a new chapter in Latin American storytelling—one that steps out from the long shadow of magical realism and the familiar narrative of perpetual crisis to offer a more nuanced, human vision of migration.

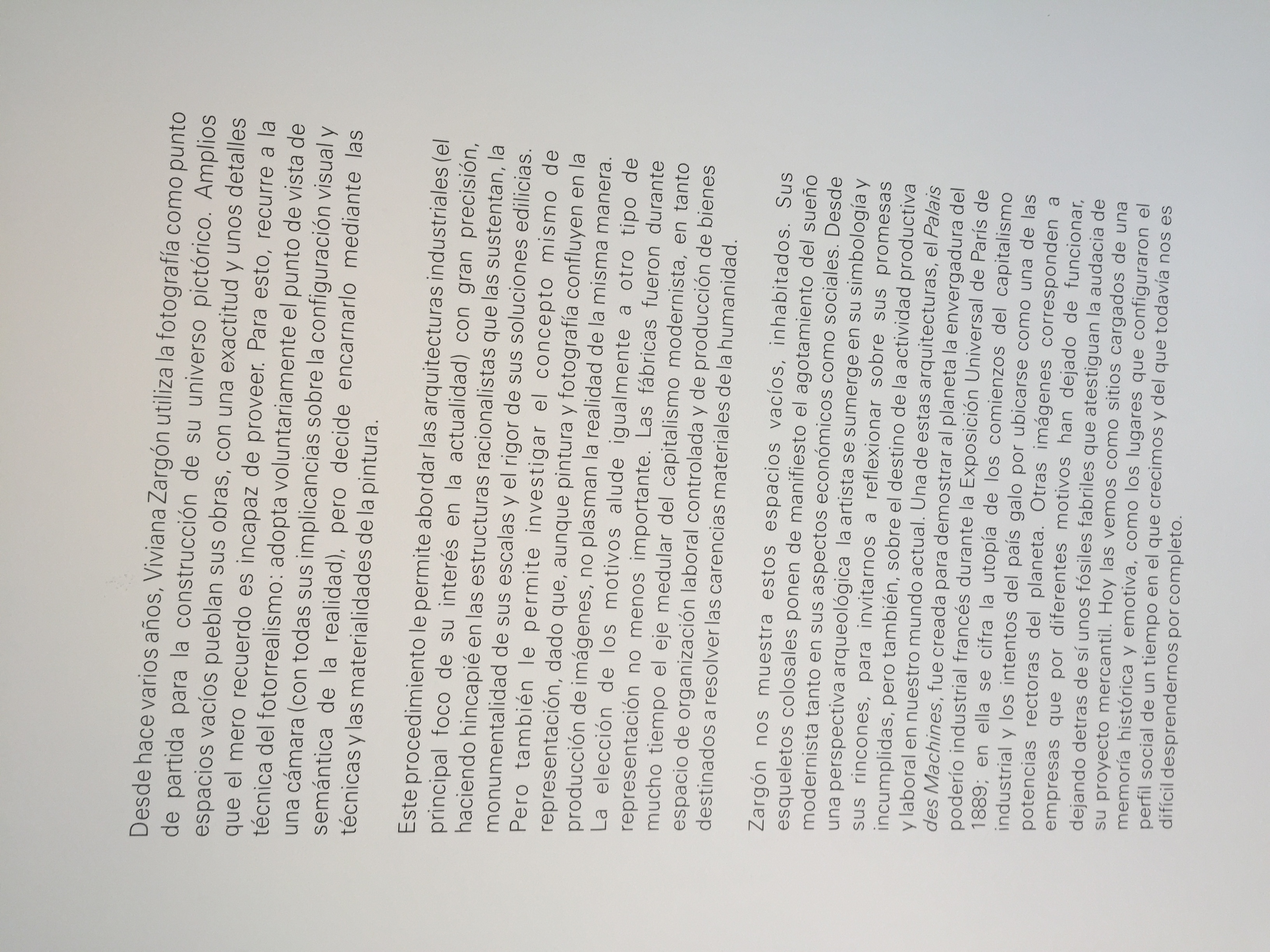

Also VISUAL ARTS AND MIGRATION

Painting the Migrant Story

When a city’s walls speak, they tell the stories power tries to erase. In Lima, street art transforms blank concrete into a living archive of migration, identity, and resistance.

My work on Visual Arts and Migration spans public art, photography, and artist interviews (stay tuned for the upcoming podcast!). I explore how creative expression—on city walls, in community spaces, and across digital platforms—shapes the way migration is seen, remembered, and imagined.

Graffiti Without Borders

Graffiti artists form a truly transnational community, weaving together people, citizenship, technology, and social movements across borders. In Lima, Peru’s capital, street artists have sparked new conversations about rural migrants’ relationship to the city—filling in the cultural gaps left by official institutions slow to embrace change.

Take the Latido Americano Festival (2013). Organized by Lima-based muralists Entes and Pesimo, both celebrated for their artistry and activism, the festival brought street artists from around the world to reimagine the old colonial city with fresh colors, bold shapes, and new symbols. Suddenly, Lima’s walls told stories the city had kept invisible for decades—faces of Indigenous migrants, Andean traditions, and hybrid cultural icons blending urban modernity with highland heritage. It was street art as public history, community identity, and political statement all at once.

When the Walls Came Down

In 2015, most of the festival’s murals were erased under the orders of then-mayor Luis Castañeda Lossio, who claimed they “did not fit” the city’s aesthetic. Whether motivated by politics, personal taste, or a narrow vision of urban beauty, the decision triggered a national conversation: Who gets to decide what a city should look like? And whose stories deserve to be seen?

Ironically, the erasure only underscored how deeply the murals had resonated with residents. Many viewed them as symbols of a more inclusive Lima—one that embraces its migrant heritage rather than erasing it.

Art as Cultural Bridge

Today, as Peru experiences a renewed sense of cultural pride, street art has become a bridge between past and present, rural and urban, marginalized and mainstream. Graffiti in Lima often carries a social agenda, tackling themes of migration, class struggle, and racial discrimination. Murals capture the realities of daily life—economic hardship, cultural mixing, and the persistence of Indigenous traditions—and return them to public view.

These works are more than decoration. They are political interventions, reclaiming space for Andean culture in the heart of the capital. They demand that we see the people who walk the city’s streets, whose stories are too often overlooked, and whose presence is the living fabric of Lima’s identity.